John Marin’s Maine

John Marin’s Maine

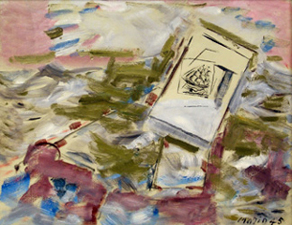

Sea Piece, 1945

Oil on canvas

In commemoration of the 50th year anniversary of the death of John Marin (1870-1953), The University of Maine Museum of Art (UMMA) will present John Marin’s Maine, from October 2, 2003 – January 17, 2004. This exhibit, which celebrates the life of Marin, chronicles the 38 years from 1914-1953, that the artist painted in Maine. The exhibition will include many fine watercolors as well as important drawings and works on canvas.

In 1870 John Marin was born in Rutherford, New Jersey. As a young man he worked in architect’s offices and from 1893-1995, as a freelance architect. During this time Marin became increasingly interested in sketching. He studied art at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia, PA from 1899-1901 and the Art Students League in New York during 1904. Living in Paris from 1905-1909, Marin made trips to Holland, Belgium, Italy and England. Although working mainly as an etcher in the tradition of Whistler, he also made a number of watercolors and pastels. Marin returned to New York in 1909 for his first one-man exhibition at Stieglitz’s Photo-Secession Gallery but returned briefly to Europe again in 1910-1911 before settling permanently in the USA. John Marin lived in Cliffside, New Jersey from 1916 until his death in 1953 while spending his summers in the Berkshires, the Adirondacks, the Delaware River country and Maine. Most of all he loved the coast of Maine, summering in Small Point or Deer Island and from 1933-1953 at Cape Split. Marin developed a more dynamic, fractured style after 1912 in his effort to depict the interaction of conflicting forces, gradually evolving summary ways of rendering his vivid impressions of sea, sky, mountains or the skyscrapers of Manhattan. Although working almost exclusively in watercolors during the 1920s, Marin painted largely in oils after 1930.

John Marin believed he had to know a place intimately before he could paint it. A particularly vocal opponent of what he considered the “self-indulgence” of pure abstraction, Marin tried to imbue each painting with his love of the visible world. One critic’s observation that Marin painted from an inner vision offended the artist deeply and was summarily dismissed by him as rubbish. Marin could not conceive of an art of consequence that was not grounded in the act of seeing. To Marin, “seeing” was a “repetition of glimpses” and each painting an opportunity to capture in a single, striking image the “eye of many lookings.” Instilled with a modernist’s distrust of illusionism, he drew on the resources of his own form of Cubism to explore his response to what he saw and experienced. Marin always insisted that his paintings be both celebrations of the visible world and flat, two-dimensional objects: “I demand of [my paintings] that they are related to experiences … that they have the music of themselves – so that they do stand of themselves as beautiful-forms-lines and paint on beautiful paper or canvas.”

Maine symbolized for Marin the power and dynamism of nature. Marin energizes the surface of his works with an expressive power that evokes the essence of a place and moment he had experienced. As is true of so much of Marin’s work, the art exhibited in John Marin’s Maine embodies the artist’s search for the equilibrium he believed could be achieved between the forces of dynamism and those of stability and order. Filled with taut energy, Marin conveys and controls explosive vitality through a rich concert of brushwork: bold strokes, dense patches of color, fluid washes, and deft lines. There is a breathless swiftness about Marin’s work, which will always make it seem as if the paint has just dried.

John Marin’s Maine is accompanied by a checklist catalog with an essay by Meredith Ward, Director of the Richard York Gallery in New York.

A Fierce and Fascinating Place: John Marin in Maine

By Meredith E. Ward

In August 1914, John Marin arrived in the town of West Point, on Casco Bay, lured there by his friend and fellow artist, Ernest Haskell. A few days after his arrival, Marin penned a letter to his dealer, Alfred Stieglitz, back in New York in which he related his first impressions: “This is one fierce, relentless, cruel, beautiful, fascinating, hellish, and all the other ish’es, place,” he wrote. “To go anywheres I have to row, row, row. Pretty soon I expect the well will give out and I’ll then be even obliged to row for water, and as I have to make water colors – to Hell with water for cooking, washing and drinking.” ¹ Marin’s grumbling notwithstanding, his letters from Maine that summer — and every summer thereafter — were filled with a sense of wonderment for the natural beauty that surrounded him, and his sheer delight in living at the edge of the sea.

Painting in Maine seems to have been, at least initially, equally challenging to Marin. He wrote to Stieglitz that first summer, “Everything I have done up here I have had to work like Hell to get …” ². But the evidence shows that his work from that first summer in Maine was incredibly innovative and, as would be the case in the years to come, captured the essence of his direct experience with the sea, sky, and shore.

Over the next four decades, Marin returned to Maine almost every summer, staying in the West Point – Small Point area, and, after 1919, in the town of Stonington on Deer Isle. The boats and the harbor on Penobscot Bay provided fertile ground for Marin, as his style continued to develop and evolve. In signature works like Pertaining to Deer Isle, The Harbor, No. 2, 1927, Marin conveys the rhythm and movement of the bustling fishing village. Visits to other locales proved equally inspiring. In the summer of 1922, on a boat trip to Mount Desert, Marin produced a series of watercolors depicting the distinctive form of the island rising from the sea. Two years earlier, Marin had been impressed by “the mountains everywhere piling up out of the sea, mountains tumbling over and into one another with curious shapes and most wonderful islands, severe, rocky, forbidding, beautiful.” ³ His watercolors of Mount Desert, done while sitting in a small motorboat off the coast, vary in tone from intensely colorful to subtly poetic, and probably reflect his observation of the island under different light and weather conditions.

In 1933, Marin spent his first summer at Cape Split. The following year, he bought a house there, where he would spend summers for the rest of his life. From that point on he continued to produce watercolors and, increasingly, oil paintings of the Maine landscape. Marin’s oils demonstrate a similar sense of immediacy to his watercolors. A painting like Sea Piece, 1945, is bursting with vigorous brushwork and dynamic energy, and yet was clearly and carefully thought out. In it, Marin has incorporated an image of a schooner that was taken directly from a sketch he made of an iron door knocker in Bangor.

Marin recorded the movement of the sea, of course, but he also saw hills, trees, and rocks as dynamic forms. He would travel up country to places like the Tunk Mountains, Centerville, and Beddington in search of new subjects. In paintings like LeadMountain, Beddington, Maine, 1952, he accentuates the rugged landscape with force lines, conveying the essence of the place as he experienced it, an experience that went beyond optical perception.

The beauty and grandeur of the Maine landscape provided Marin with some of his greatest artistic inspiration, and some of his happiest moments. He communicated his love of Maine and its natural beauty in an early letter to Stieglitz. In reading his words, it is not difficult to imagine how Marin was able to translate this passion into some of the most powerful and poetic American paintings of the twentieth century:

Wonderful days. Wonderful sunset closings. Good to have eyes to see,

ears to hear the roar of the waters. Nostrils to take in the odors of the salt,

sea and the firs. Fish fresh, caught some myself. Berries to pick, picked

many wild delicious strawberries. The blueberries are coming on. On the

verge of the wilderness, big flopping lazy still-flying cranes. Big flying eagles. The solemn restful beautiful firs. The border of the sea.

Good night. 4

Notes:

1 Herbert J. Seligmann, Letters of John Marin (1931), from West Point, August 7, 1914.

2 Ibid., from West Point, September 16, 1914.

3 Ibid., from Stonington, September 20, 1919.

4 Ibid., from Small Point, July 31, 1917.